During the Covid 19 pandemic, Korean popular culture has not only not stopped but also shown incredible growth. Not to mention the unexpected success of BTS, the remarkable achievements of Korean cinema led by director Bong Joon Ho, along with Korean films and TV shows that are widely received worldwide through the Netflix platform, proving that the Hallyu wave is no longer just an East Asian phenomenon but has spread worldwide. What is Hallyu, let’s find out with C-Korea!

A small peninsula located at the easternmost tip of the Eurasian continent, surrounded by superpowers and divided into north and south, is the last country in the world still suffering from the consequences of the Cold War. The small country, once known for its image as a developing country with a miraculous economic growth rate, has now become a cultural exporter that resonates globally alongside other major countries such as China and the United States.

In parallel with that process, the number of students around the world wanting to go to Korea and learn Korean is increasing rapidly, Korean is no longer just a subject in foreign language courses, but has become a separate major in universities. K-pop album sales are changing the rules of the popular music industry, which were set by the United States in the digital music era.

Although overshadowed by the massive success of groups like BTS, Blackpink, and TWICE, most of the most popular K-pop groups in Korea have larger fandoms overseas. Making it onto the Billboard 100 and 200 charts, which used to be a big deal in the Korean press a few years ago, is now commonplace.

Netflix, which began offering its services in Korea in 2016, is increasingly investing in original productions in the country to bolster its Asian subscriber base. However, this has led to a significant expansion of the global consumer base for Korean content. According to the author’s research based on the “Daily Top 10” program in countries in 2020, Korean dramas ranked 5th in the world, and Korean dramas ranked 2nd after American dramas, far surpassing British dramas, which ranked 3rd, with nearly double the viewership.

Not only Netflix, but also Disney and Amazon – global OTT platforms based on subscription models – are also targeting the world market, and like Netflix, they also plan to leverage the strength of Korean content in various ways. Although there are concerns that the investment of these platforms may have a negative impact on the domestic cultural industry, as long as K-pop, Korean cinema and television continue to maintain their current cultural, social, and political energy, the future of Hallyu content will remain bright.

First, Hallyu is not a phenomenon of propagation but of reception. The phenomenon of popularizing Korean popular culture abroad began in the late 1990s, when good news from abroad was suddenly transmitted to the Korean people.

Koreans, who are often critical of domestic dramas, are surprised to see why foreigners love them, especially when Japanese dramas are better produced but not as popular.

Each country loves different Korean dramas and artists for different reasons. However, after eliminating the differentiating factors, the common reasons given by fans are factors such as the feeling of “Jeong” (情, an emotional attachment characteristic of Korean culture), concern for others, and Confucianism.

This shows that Hallyu is a phenomenon of reception, rather than a cultural phenomenon that was spread in a planned way, even in East Asia, where Hallyu was first recognized.

The growth of the Korean cultural industry is a result of democratization in the 1980s and the removal of cultural restrictions in the 1990s, which created the free creative environment necessary for cultural development, rather than the result of any planning or support.

However, this is obvious to Koreans, but the majority of foreign diplomats, journalists, critics, scholars, and civil servants still strongly believe that “Hallyu is a product of the support of the Korean government.” They believe that just as Korea developed its economy through five-year plans, Hallyu is the result of the policy of promoting the cultural industry in the late 1990s.

The belief that Hallyu is the result of government support is so strong that, even when hearing the author assert that Hallyu is a phenomenon of reception, some people still ask: “So what kind of support policy did the Korean government have to achieve this success?”

The reasons for this belief are varied. Part of the reason is that the Korean government has overemphasized the role of the state in foreign relations and expanded the scope of support for civil cultural activities in diplomacy. For example, in the process of supporting spontaneous Korean film festivals abroad, these events have gradually been transformed into activities of local Korean cultural centers.

The strategy of “soft power”, which was introduced by the United States after the Gulf War to adjust its diplomatic strategy based on military power, has been applied in Korea. This has made the role of the state in transnational cultural flows more prominent, sometimes creating a counterproductive effect.

In fact, discussions of “soft power” in the United States are a viable policy because the country does not need a clear state presence, but in Korea, the application of this idea has made the role of the government too prominent in civil diplomatic activities. This requires reflection, especially when Korea is at a point where a new approach is needed.

In other words, Hallyu is not the result of government support for cultural exports but rather the result of the natural cultural development and cultural capacity of the Korean people. Korea’s cultural diplomacy needs to be adjusted to affirm that Hallyu’s success stems from its own development, not government intervention.

Korea, despite joining the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and being considered an advanced country, has not yet been fully recognized by other countries for its cultural capacity. This is reflected in the fact that other countries still do not consider Korea as a culturally advanced country capable of influencing the world.

Meanwhile, countries like France with its large cultural budgets, Japan with its “Cool Japan” program, or the UK with its creative industries, are not considered the result of government support. However, when it comes to South Korea, the belief in government support clearly shows the remaining colonial mindset.

From this perspective, Hallyu has global historical significance. It proves that even a country that did not accumulate its initial wealth through colonial exploitation can possess cultural capacity and become a cultural center, captivating the world with cultural content developed through democratization. For citizens of developing countries, South Korea is a model of a future they can dream of.

Second, while the Korean government has made an excessive effort to tie Hallyu to the national image through public diplomacy, in reality, the content of Hallyu – the “K” factor – is constantly changing.

With the internationalization of the cultural industry, Korean production companies, which have gained credibility in their production capabilities, are now receiving offers for collaboration and production from American broadcasters and platforms. This has been clearly demonstrated by investments from Netflix.

Even bigger changes are occurring within K-pop itself. In 2016, an experimental group called “EXP Edition” consisting of American members debuted. This led many K-pop fans to criticize that the group could not be considered K-pop due to differences in race, language, and region. However, these arguments gradually became obsolete as Korean entertainment companies began creating idol groups consisting entirely of foreigners through audition programs held overseas.

Furthermore, even without direct intervention from the K-pop industry, K-pop’s influence is still strong around the world. In many places, idol groups created through local audition programs often have a cultural style so similar to K-pop that, except for the language factor, they are difficult to distinguish from Korean groups.

In light of these phenomena, the question of “What does the K in K-pop really mean?” has been raised in academic circles. As a result, K-pop has increasingly evolved in a way that is not exclusively tied to Korea, although no one in the world can deny that K-pop originated in Korea.

This expansion requires Hallyu producers and the Korean government to adjust their approach. Hallyu now has a meaning that goes beyond local borders, becoming a phenomenon of particular importance in world history. It is time for a more nuanced and professional approach, both industrially and diplomatically, to ensure that Korean popular culture is seen as an opportunity rather than a threat to the restructuring of the cultural system in the 21st century.

Third, the Hallyu and K-pop phenomena are often interpreted as female and Millennial (Gen Z) fandoms, or even as a phenomenon of cultural minorities. This is based on research on Hallyu and K-pop fans, as well as on the actual distribution with significant participation of women and young people.

However, using such a narrow interpretation creates prejudices and misunderstandings, which stereotype Hallyu fans. Put bluntly, K-pop is often associated with images of passionate female teenage fandoms, middle-aged housewives who watch television, or multicultural youth and minorities who are marginalized in the Western mainstream.

Where these stereotypes come from, and what discourses they are influenced by, cannot be explained in detail in this article. Instead, however, the author summarizes recent perspectives in Hallyu fan studies.

Hallyu and K-pop fandom, regardless of their origins and development in their own national contexts, are a prime example of a transnational cultural phenomenon in the age of globalization and digital culture. This is the intersection of digital participation culture, the evolution of globalization, and the racial, gender, and generational issues of Generation Z with a more inclusive gender sensibility.

Hallyu fans enjoy content like dramas and K-pop not because they are entirely politically correct, but because they provide fresh, creative, and inspiring elements to generational, racial, and gender issues in an artistically appealing form.

Furthermore, the success story of Korea and its historical significance have prompted young people around the world to see K-pop as a symbol of solidarity in political movements. From the “Black Lives Matter” (BLM) movement in the United States, protests in Hong Kong and Chile, to conflicts in Israel and Palestine, the presence of K-pop has been summoned as a means of support.

Fourth, the cultural industry framework of Hallyu is shaped by the intersection of many East Asian pop cultural influences, rather than a product developed in secret in Korea’s isolation.

History has proven that culture develops through open communication, and that widely spread cultures are enduring. Even without tracing back to the early 20th century, when Korean movie stars like Jin Lin were already present in the Chinese film industry, we cannot deny the great influence of Hong Kong cinema and music in the 1980s and 1990s. This was followed by comics, animation, television dramas, J-pop, and especially Japanese idol culture, all of which played an important role in shaping the content of Hallyu.

In addition, direct influence from the United States, starting with the presence of the US military after the Korean War and increasing in the 1980s, helped shape the prototype of today’s K-pop, as seen in the Seo Taiji phenomenon in the early 1990s.

However, with the rise of Hallyu, online nationalism between Korea, China, and Japan has become increasingly worse, leading to erroneous views and distortions of the origins and cultural characteristics of Hallyu. For example, the drama Joseon Exorcist (조선구마사, SBS, 2021) was discontinued after two episodes due to strong criticism from Korean netizens for its use of Chinese elements and historical distortion.

Amid tensions between Korea and Japan, the confrontation between netizens of the two countries has also escalated. Documents about the formation of K-pop often only mention the influence of American popular culture, while avoiding mentioning the contribution of Japanese popular culture to avoid attacks from online nationalist forums.

As mentioned earlier, the “K” in K-pop is no longer the exclusive property of Korea. Yet, none of the world’s Hallyu consumers are unaware that K-pop originated in South Korea.

The expansion of Hallyu requires governments and content producers to change their initial attitudes and recognize that Hallyu has gone beyond its original regional understanding and has a special significance in world history. This is where more sophisticated and specialized strategies, both industrial and diplomatic, are needed. It is important to ensure that Korean popular culture is not seen as a threat to the restructuring of the cultural system in the 21st century, but as an opportunity.

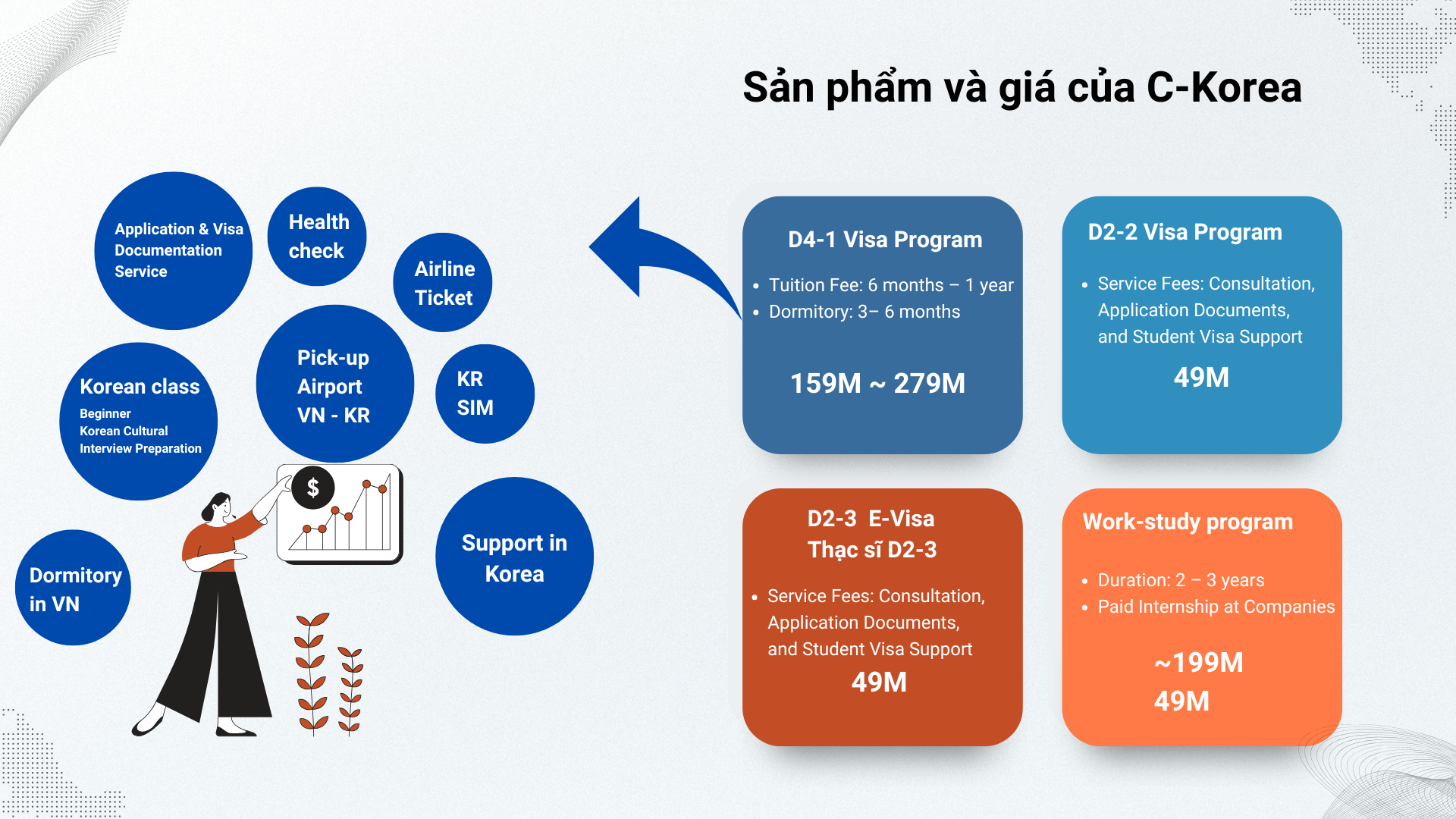

For more information about studying and working in Korea , please contact :

C-KOREA CULTURE AND STUDY ABROAD CONSULTING CO ., LTD.

- Address : 5th Floor , 94-96 Nguyen Van Thuong , Ward 25 , Binh Thanh District , Ho Chi Minh City

- Hotline: +84 28 7308 4247

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/duhochanquocckorea/

- Tiktok: https://www.tiktok.com/@duhoc_ckorea

- Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/@Duhoc_ckorea